Published on the 11/06/2020 | Written by Jonathan Cotton

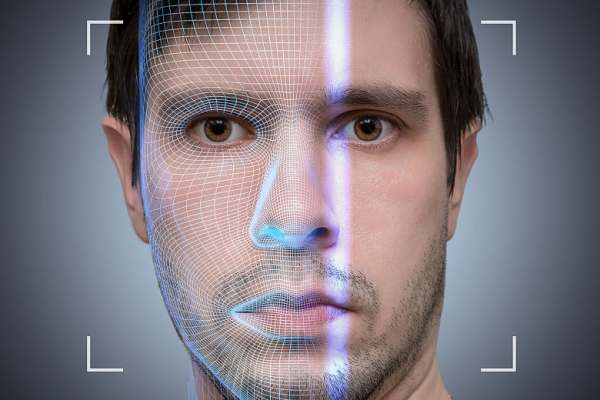

New face-matching tech uses algorithms to spot border crims…

Australia has launched a new biometric ID border processing system, developed for the Department of Home Affairs by Unisys, which will provide biometric identification border processes for visitors to the country – of which there were 9.5 million last year.

The contract, worth around AU$44 million at the time, was won two-and-a-half years ago as part of the Department’s move toward better processing of travelers and improvements to Australia’s ability to identify criminals and ‘persons of national security interest’.

Built on Unisys’ identity management and authentication tech, the awkwardly titled ‘Unisys Stealth(identity)’, supports fingerprint, face, and voice, as well as ‘behavioural biometrics’, with the ability to integrate new features and functionality in the future.

“We can do better with getting the balance right.”

Unisys says the new Enterprise Biometric Identification Services system (EBIS) is one of the most accurate biometric identity management systems in the world today. Not only that, it’s much needed, with the number of travellers passing through Australian border control likely to increase on previous years, once the Covid-19 pandemic passes.

“The long term growth in the volume of travellers that will hopefully return after Covid-19, as well as the increased risk of potential terrorist or fraudulent activity, means that effective border security is more important than ever,” says Rick Mayhew, VP and GM of Unisys APAC.

Unisys says that the system can handle more than 100,000 transactions daily.

“EBIS provides Home Affairs with greater confidence in verifying an individual’s identity for efficient and early detection of criminals and persons of national security concern who change names and obtain passports using false identities.”

The system – which can also be tailored to include iris recognition if required – uses biometric matching algorithms developed by French company Idemia to find fingerprint and face matches. That company is also one of the parties awarded a new contract to deliver Europe’s forthcoming Entry/Exit System, currently under management by the excruciatingly-named Agency for the Operational Management of Large-Scale IT Systems in the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice (eu-LISA), which, when completed, will likely be one of the largest of its kind in the world.

Both Australia and the EU’s new systems are just two instances of the global trend of facial recognition tech rollout. In Spain, cameras and software that can process 16,000 facial points are now being included in some ATM machines, and let users withdraw money without the use of a PIN code. Similarly, some Brazilian POS systems will soon be using facial recognition tech to identify users, with 800,000 locations using the system before the end of the year.

In New Zealand facial recognition technology is apparently finding enthusiastic adoption (though not necessarily reception) with the recent revelations that such systems are already in use at some Foodstuffs supermarkets and Auckland’s Sky City.

Not everyone is as enthusiastic about the rapid proliferation of facial recognition tech of course. While matching faces with fingerprints at the border has its utility, the potential for abuse, error and privacy breaches has some worried.

“It’s one thing to fast track border immigration controls with facial recognition technology but relying on CCTV street cameras to accurately match faces to passports and driver’s licences is inherently risky,” says UniSA senior law lecturer Sarah Moulds.

“Using FTR [facial recognition technology] in a controlled, consent-based environment like an airport or customs office to confirm identity from a passport photo is not a major concern because of the quality of the data.”

Moulds says that the recent rejection of Australia’s controversial Identity Matching Laws proposal by the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Safety is a timely reminder that privacy safeguards are there for a reason – and it’s not to stifle innovation.

“When DNA testing first came in, juries were (wrongly) convinced it was infallible,” argues Moulds. “We’re at the same stage with FRT where people believe it is accurate when in fact it has the same potential weaknesses as many other things, such as finger printing or handwriting.

“The committee is not strictly rejecting facial recognition technology out of hand, but indicating we can do better with getting the balance right.”