Published on the 20/06/2024 | Written by Heather Wright

Buying and selling data to the highest bidders…

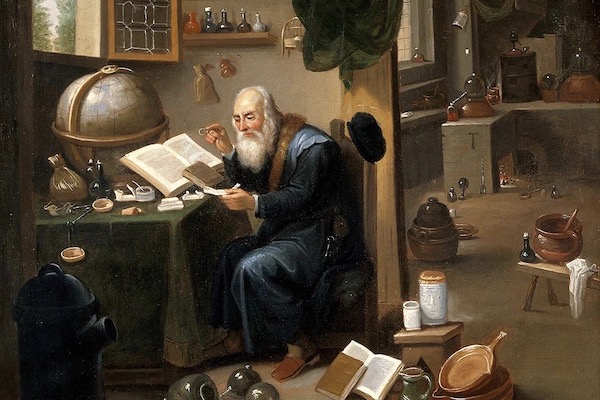

“I call them the data alchemists of the modern world. They are basically mining and refining all sorts of data about us and then curating it and selling it to the highest bidder.”

That’s Chandni Gupta, deputy CEO and digital policy director at Australia’s Consumer Policy Research Centre (CPRC), talking about data brokers – a lucrative, but relatively unknown, part of the data ecosystem which is raising concerns.

“You’d be getting whatever you want from them basically.”

Quantium – which has first party data derived from 10 million customers from Australia’s largest retailer via its Q.Checkout insights tool – and Experian are among the big players in the A/NZ data broking market (though most rush to distance themselves from the ‘data broker’ title) but there are plenty of others including CoreLogic, Equifax, illion, LiveRamp and Nielsen.

“They’re often companies that as individuals we wouldn’t even recognise,” Gupta told iStart.

“They have partnerships with larger businesses, and you’ll have businesses sharing the information with data brokers and the data brokers sharing information back from other points of collection to the business.”

She says data brokers are offering an endless stream of data for businesses willing to pay – and willing to pay they are.

“You’d be getting whatever you want from them basically.”

A recent report by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) makes it clear larger companies are procuring from data broking businesses, or are in partnership with those ‘trusted partners’ or trusted data partners.

“It is happening at scale,” Gupta says.

The ACCC report says banks, fintech companies, Buy Now Pay Later providers, private equity firms and superannuation funds are accessing a range of data products and services from data firms, for a range of purposes, including verifying identity or income of customers, streamlining credit assessments, reducing fraud risk or learning about spending behaviours, preferences and trends.

For retailers, data services are being used to improve data-driven marketing and advertising projects. LiveRamp’s Safe Haven data clean room environment is used by FMCG and retail businesses to compare and match their own first-party data, including transactional data, to generate new audience insights and optimise reach.

(In March digital rights advocate Open Rights Group submitted complaints to France’s data protection authority alleging LiveRamp’s profiling system links browsing activity to personal identity and that the company processes personal data ‘without a legal basis’.)

While data might be 21st century oil for business, enabling them to innovate and develop new or better services, tailor offerings and advertising more effectively, retain existing customers and set prices and maximise profit, or be used in risk mitigation and fraud detection, there are plenty of potential harms too.

Gupta says it’s not the specific data being collected that’s the concern – it’s what can be done with the data.

“When you aggregate data across multiple data sets what you find is a business can use that data to find out what you’re excluded from, what you get to see or what is offered to you – or even what price you pay for something. That’s the concern: How your vulnerabilities can be exposed and manipulated as a result of organisations having that information about you.”

The ACCC says it’s concerned about the growing risk of consumers being re-identified as datasets are combined with additional data points, and the potential identification and targeting of vulnerable consumers when consumers are categorised into groups to enable businesses to identify potential customers.

It cites the example of a consumer segment identifying people as ‘frequent gamblers’.

Gupta shares an example of de-indentified transactional data from National Australia Bank, shared with Quantium, which was then linked with data from SportsBet.

“I don’t need to spell that out as to what it ends up doing. And it is that drawing the bow between where potential vulnerabilities could be exposed and exploited in a way that leaves people far worse off.”

In 2023 a dataset covering 650,000 Australian and international customer segments was discovered on the site of Microsoft advertising platform Xandr. Among the lists of consumers Reset.Tech Australia identified within the dataset which sparked concerns were lists of people deemed ‘financially unsavvy’, indigenous Australians, minorities, elderly people living alone and those experiencing financial difficulties and distress.

The ACCC report says while Microsoft says the dataset is no longer used, it’s a good example of the types of consumer segments that may be used by data firms.

In 2021, data broker Epsilon settled with the US Department of Justice to the tune of US$150 million, after it was found to have facilitated fraud schemes targeting elderly consumers by selling modelled lists of US consumers who it identified as likely to be susceptible to such schemes.

The CPRC released research earlier this year about data broking – and the distaste and concern Australians feel for collection and sharing of their data, with 71 percent saying they believe they have little to no control over businesses sharing personal information with other businesses.

It’s a similar story in New Zealand, where a survey by the Office of the Privacy Commissioner, released last month, showed 80 percent of Kiwis want more control and choice over the collection and use of data and 82 percent want the right to ask a business to delete their personal information.

That feeling of having little to no control over businesses sharing personal information with other businesses – including data brokers – is valid.

With Australian privacy law based on notice and consent, information about data collection can quickly be buried in terms and conditions and very long privacy policies. Decline to agree to those conditions, and you will often find yourself out in the cold.

“The only way out at the moment often is to not use the product or service, but that leaves an individual with very little genuine choice. It is very much a take it or leave it approach,” Gupta says. “There’s a real power imbalance. Either you say no to almost every product and service you want to consume, or you give up your data.”

As to the data being collected – it’s endless.

“If a data point can be collected or tracked, it can be shared,” Gupta notes.

The ACCC report, notes the breadth of data being collected, from our web searches and the content we’re viewing and products we’re purchasing to whether we searched from a mobile phone or desktop, or via voice-assisted search, the mode of transportation we preferred, how long we watched something for, the time of the day we made a purchase.

“This data also forms records of our on- and offline behaviours and preferences, and can be collected, processed, analysed, sold and shared,” the ACCC report says.

Brokers are also collecting, analysing and aggregating data from sources such as court records, census data, property and motor vehicle records and commercial sources such as credit card companies. Renters can find themselves forced to use a particular platform and as part of that must agree to their data being used.

“You can imagine how much you share when putting in a rental application and what can be done in that space,” Gupta says. “The real estate agency may not necessarily be the one collecting or sharing, but they are facilitating it by making it the preferred or quickest option for you to be one of the preferred candidates.”

Back in 2019, the ACCC found some loyalty schemes were earning as much as $374 million a year from selling customer data. In New Zealand, AA Smartfuel acknowledged it was selling aggregated data to its partners, but said it was only getting ‘less than $40,000’ in return.

Gupta says current laws fall short in covering the issue of data brokers and the buying and selling of consumer data.

“The definition of personal information is very narrow, and the data brokers are using quite vague terminology to work around that definition. The language is designed to really keep consumers in the dark. There is no standard definition in Australia, for example, for terms like pseudonymised information, anonymous information, hashed email address. These are all points of data that can single you out from a crowd.”

For Gupta, part of the problem lies in an inability to know whether companies are using, sharing and collecting the information for good reasons versus collecting it to exploit individuals or groups.

“It’s really hard to tell the difference at the moment because the law at the moment doesn’t have that level of protection.”

She says two changes would make a difference. The first is strengthening privacy protections to make it clear what data can be collected, shared and used.

She’s also keen to see the introduction of a law against unfair business practices, holding organisations accountable for what they do with data and whether their usage of it leads to unfair outcomes.

“In Australia we have laws that protect us from businesses lying to us and we have laws that protect us from businesses doing really egregious practices, but we have nothing in the middle. So at the moment, unfair isn’t actually illegal, and that’s what makes it a really difficult space for you to tell the difference whether a business is actually collecting that information to do good or to do harm.”

Australia’s Privacy Act is currently undergoing reform.

“The proposal on the table at the moment is the ‘fair and reasonable’ test and that will certainly get us much further than we are at the moment to show that data is being collected, shared and used in a way that is fair and reasonable. But fair and reasonable still leaves a slight gap, because fair and reasonable could be for business practices.

“It’s a step further, but ideally further down the track you’d want to go down the path you see in sectors like finance and health, where there is a duty of care and an expectation that you’re doing right by an individual or community.”

Fo now, though, Gupta is calling on organisations to really consider where data is coming from, how it is being collected and what it will be used for.

“If it is leading to communities having unfair outcomes as a result of it or you’re exploiting someone’s vulnerability, and you’re putting profit over that, then you really need to reconsider how what that means for your business model,” she says.

“We are at a point in time when we need the laws to change and we need businesses held accountable for what they are collecting, how long they are keeping it for, how they are sharing data and what they are using data for. We’ve gone quite long now waiting to see if businesses would course-correct, and that hasn’t been the case. Now we need obligations so there is a clear expectation for all businesses.”