Published on the 08/04/2020 | Written by Heather Wright

It’s got our data already, so why not use it for public good?…

If you have ever wondered about the quantity of data Google holds on our daily movements, wonder no more. The tech behemoth’s newly launched Covid-19 Community Mobility Reports highlights just how much it knows about where we’re going and when.

The tracker, launched last week for 131 countries, harnesses the granular location data Google collects and usually uses to show us things such as traffic hotspots and how busy stores are at particular times of the day – not to mention for the ubiquitous ad-targeting.

“Aggregated, anonymised data could be helpful as they make critical decisions to combat Covid-19.”

This time, however, the data is being used to show how visits and the length of stay at different places have changed under social distancing guidelines and lockdowns.

The Covid pandemic has seen a governments and health agencies scrambling for tools and data to help with their responses to the threat. The Covid-19 Community Mobility Reports are Google’s response, albeit the company is at pains to say the reports are just to help public health officials understand responses to social distancing guidance and are not for medical diagnostic, prognostic or treatment purposes (just in case we were confused about that!).

“In Google Maps, we use aggregated, anonymised data showing how busy certain places are – helping identify when a local business tends to be most crowded,” says Jen Fitzpatrick, Google SVP, Geo.

“We have heard from public health officials that this same type of aggregated, anonymised data could be helpful as they make critical decisions to combat Covid-19.”

Google says it hopes the reports will ‘help support decisions about how to manage the Covid-19 pandemic’.

“This information could help officials understand changes in essential trips that can shape recommendations on business hours or inform delivery service offerings.

“Similarly, persistent visits to transportation hubs might indicate the need to add additional buses or trains in order to allow people who need to travel room to spread out for social distancing.

“Ultimately, understanding not only whether people are travelling, but also trends in destinations, can help officials design guidance to protect public health and essential needs of communities,” Fitzpatrick says in a blog announcing the offering.

“Ultimately, understanding not only whether people are travelling, but also trends in destinations, can help officials design guidance to protect public health and essential needs of communities,” Fitzpatrick says in a blog announcing the offering.

Some aspects of the data, however is, by Google’s own admission, ‘incomplete and insufficiently granular’.

The company this week told iStart the product wasn’t designed to provide robust or high-confidence records for medical purposes, such as contact tracing. It says the data couldn’t be adapted to contact tracing.

When asked if there was scope for Google to harness Bluetooth to gather proximity data, a la Singapore’s TraceTogether app, the company would say only that the reports use location history data for aggregated, anonymised insights to measure the impact of social distancing measures ‘therefore BLE is not relevant for this purpose’.

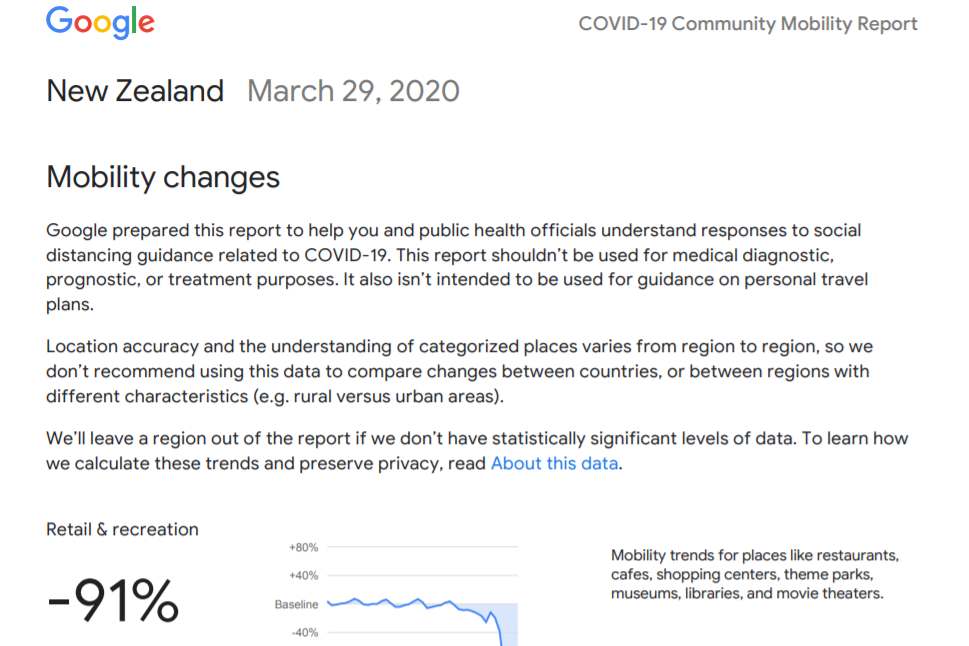

Certainly, the data available to the public is high level only – no doubt to avoid a firestorm of privacy complaints. It shows retail and recreation movements for the period to Sunday March 29, down 91 percent in New Zealand, which remains under a Level 4 lockdown, limiting all but essential sales and services. Grocery and pharmacy – two categories allowed in New Zealand, have also taken a hit, at least on the movement side, down 54 percent, no doubt as people shop less, but buy more in one hit. In Australia, where lockdown is less strict, retail and recreation are down 45 percent and grocery and pharmacy down 19 percent.

Italy, which continues to be among the hardest hit, saw retail and recreation down 94 percent and grocery and pharmacy mobility down 85 percent.

The privacy question

The data being used is data we are already giving away, and the depth of that data collection should come as no surprise. It’s the data Google pulls from us constantly – every time you use a location dependent app. While the company notes that Location History is off by default (and that you can choose to turn it off at any time or delete history data from your Google Timeline), if you want to use an app using location services, such as Google Maps, you’re likely to need to have Location Services on. In February Google noted that more than one billion peope worldwide are using Google Maps

(If you want to give yourself a wake-up call as to how much of a trail you’re leaving, on an Apple device go to Settings>Privacy>Location Services>System Services>Significant Locations. If you’ve got Location Services on you’ll see a list of all the places you’ve visited. It’s reportedly one of the methods the Ministry of Health’s contact tracing centre has been using to manually trace where Covid patients have been, and who they might have been in contact with. And yes, it records it down to physical addresses – albeit, not always completely accurately: I’ve apparently been visiting a house two houses away from my own on a regular basis…)

Back to Google: It says the Community Mobility reports are ‘powered by the same world-class anonymisation technology we use in our products every day’. (No mention of the 50 million Euro fine from France’s data protection regulator, CNIL early last year for failing to provide enough information about data consent policies or give users enough control over how information is used.)

The insights in the reports are created with aggregated, anonymised sets of data from users who have turned on the Location History setting.

Google says it’s using differential privacy, which adds artificial noise to the datasets ‘enabling high quality results without identifying any individual person’.

Google says it is also collaborating with ‘select’ epidemiologists working on Covid-19 with updates to an existing aggregate, anonymised dataset that can be used to better understand and forecast the pandemic.

“Data of this type has helped researchers look into predicting epidemics, plan urban and transit infrastructure, and understand people’s mobility and responses to conflict and natural disasters.”